Fed Independence, Dollar Dominance, and Mispricing US Institutional Risk

Markets price the resilience of the dollar-based global financial system, while discounting institutional erosion at home and a foreign policy that tests alliances and the rules-based order.

Fed chair Jerome Powell having to issue an official statement saying that President Trump is using the threat of criminal charges to pressure him over monetary policy is extraordinary. It is hard (if not impossible) to recall a modern instance in which a central bank governor in an advanced economy has been pressured in this way. The fact that Jay Powell he felt compelled to say it out loud is itself information about how serious the situation has become. Powell says the administration has threatened criminal indictment and issued subpoenas in an attempt at pressuring the interest rate decisions of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The Trump administration is effectively weaponising the Department of Justice to intimidate the FOMC by threatening criminal proceedings.

Trump was already poised to replace Powell within months, as Powell’s term as chair ends in May 2026 (even though Powell could remain on the Board after that). So this is 1) petty retaliation against a Fed chair seen as insufficiently compliant, and 2) an attempt to intimidate the whole FOMC to lower interest rates under the threat investigatory pressure. With Powell and Lisa Cook, two members of the FOMC are now facing criminal investigation.

Political pressure on the Fed is not necessarily new. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson clashed with Fed Chair William McChesney Martin after the Fed voted to raise the discount rate, a tightening Johnson feared would jeopardise his domestic agenda. A bit later, on the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon repeatedly pressured Fed Chair Arthur Burns to engage in expansionary monetary policies in the run-up to the 1972 election. But those episodes were primarily political arm twisting, and in Nixon’s case, electoral pressure backed by patronage and the ambient threat of replacement. What is new here is the prosecutorial pressure to the President’s dissatisfaction with monetary policy, which signals that the perceived constraint set around central bank independence has weakened considerably.

Why does this matter for markets? Stronger central bank independence is associated with lower and less volatile inflation. The point is not that technocrats are magically better, but rather that independent institutions can act as a check against the temptation to use surprise inflation or overly loose policy for short-run political gain. Once investors begin to believe that monetary policy is becoming a political instrument, inflation expectations, term premia, and risk premia can adjust in ways that are difficult to reverse.

And yet, markets appear oddly calm in the face of visible institutional erosion and geopolitical stress. The market reaction to Trump’s attacks on the international system, the role of the dollar, the attack on Venezuela, and his threats to invade Greenland has been relatively muted so far. However, it is hard to see markets simply shrugging off an assault this direct on central bank independence. However, if the Trump administration’s actions were or are expected to fundamentally alter the risk profile of US assets and the dollar, why do we not see more signs of a collapse in the dollar or a sustained buyers’ strike in Treasuries?

Why markets can look through institutional stress

One answer is that harmful domestic governance trends do not mechanically translate into the loss of the dollar’s and Treasuries’ global roles on any short horizon. The dollar system is sustained by path dependency and network effects, the US lingering role as lender of last resort, and by the lack of close substitutes at scale. That equilibrium can be surprisingly resilient in the face of political deterioration, until it is not.

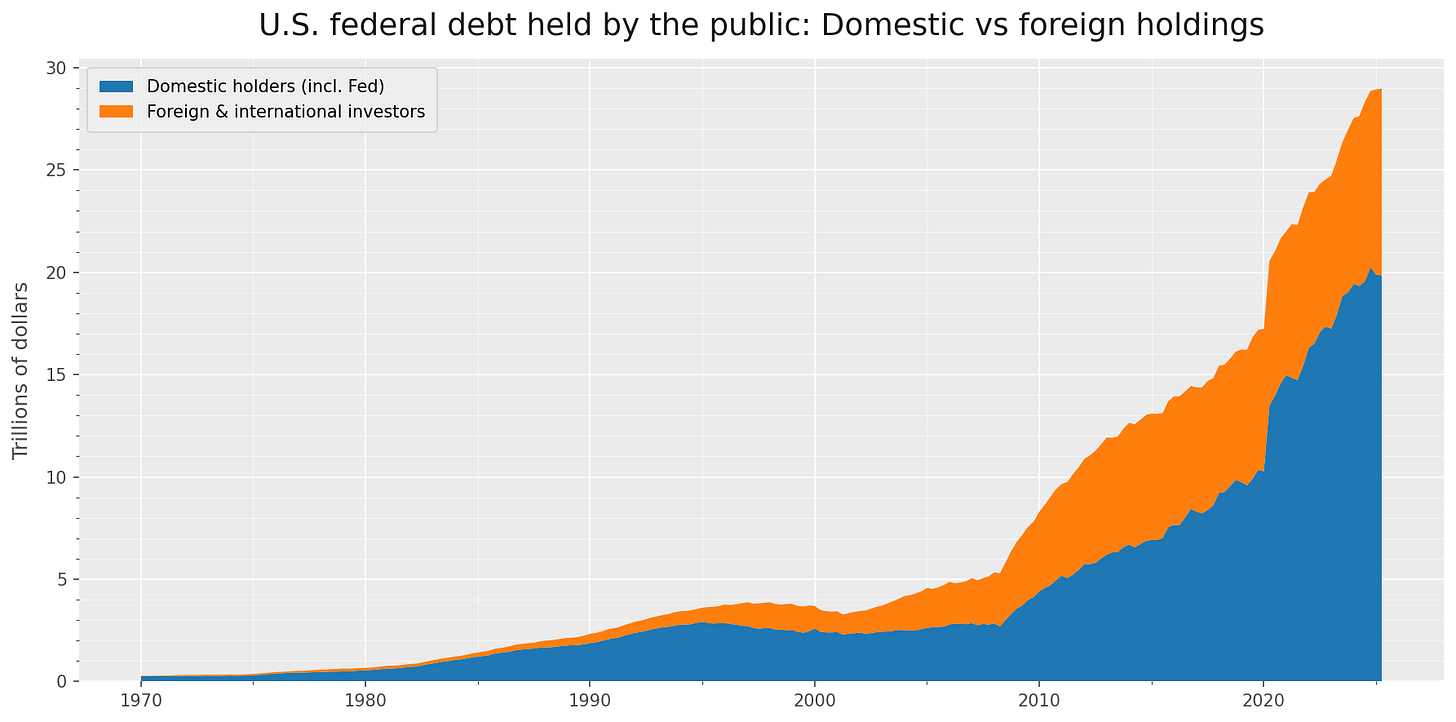

Start with the composition of holders. Foreigners own a large share of Treasuries, but still a minority share. They also own minority shares of most big US asset classes. The US Treasury annual survey on foreign portfolio holdings of US securities estimates that foreign investors own about one-third of marketable Treasuries, roughly a bit over one-quarter of US corporate debt, and under one-fifth of US equities outstanding. That means that the marginal seller is trying to exit a market in which the marginal buyer is often domestic (households, mutual funds, pensions, insurers, banks) unless foreign investors can collectively reallocate into a comparable non-US asset pool.

Then consider the substitution problem. A reserve currency system requires a large, elastic supply of safe, liquid claims that foreigners can accumulate. According to the Triffin dilemma, global demand for safe claims grows with the world economy while credible supply is concentrated in a small set of states with the fiscal and institutional capacity to issue at scale. Supplying the world with reserve assets is therefore often linked to persistent external deficits by the reserve issuer. That logic implies that if the world wants fewer dollar safe assets, it must want more non-dollar safe assets. For that to happen at scale, some other issuer would need to supply them, typically by issuing more widely accepted safe public debt and being willing to absorb net foreign demand for its liabilities.

The euro area is the most plausible competitor, but it still lacks a single euro area-wide safe asset comparable to US Treasuries in depth and liquidity. German Bunds are the closest analogue, but the stock is far smaller than the US Treasury market, and sovereign issuance in the euro area remains nationally fragmented. Europe’s financial markets are also generally smaller and less liquid than those of the US, with less depth in market-based finance, securitisation, and corporate credit. At the same time, the euro area has tended to run current account surpluses in aggregate. A current account surplus means that, in net terms, Europe exports capital rather than importing it, and building net claims on the rest of the world. Turning the euro into a true dollar substitute would require the euro area, or issuers within it, to supply a much larger stock of safe, liquid euro liabilities to the world.

Other candidates are simply too small. Take the Swiss franc. Switzerland is the archetypal safe haven and the the Swiss franc is commonly considered a strong currency that serves as a safe asset in crisis periods. However, Switzerland’s government bond market is not remotely large enough to absorb a large share of global demand, and the Swiss National Bank has historically leaned against appreciation by buying foreign assets, much of which ends up being US securities, including US equities.

Gold is also not an equivalent substitute either. Gold can absorb some diversification demand, but it cannot replace the functional role of Treasuries as the benchmark risk-free curve and the core collateral instrument in secured funding.

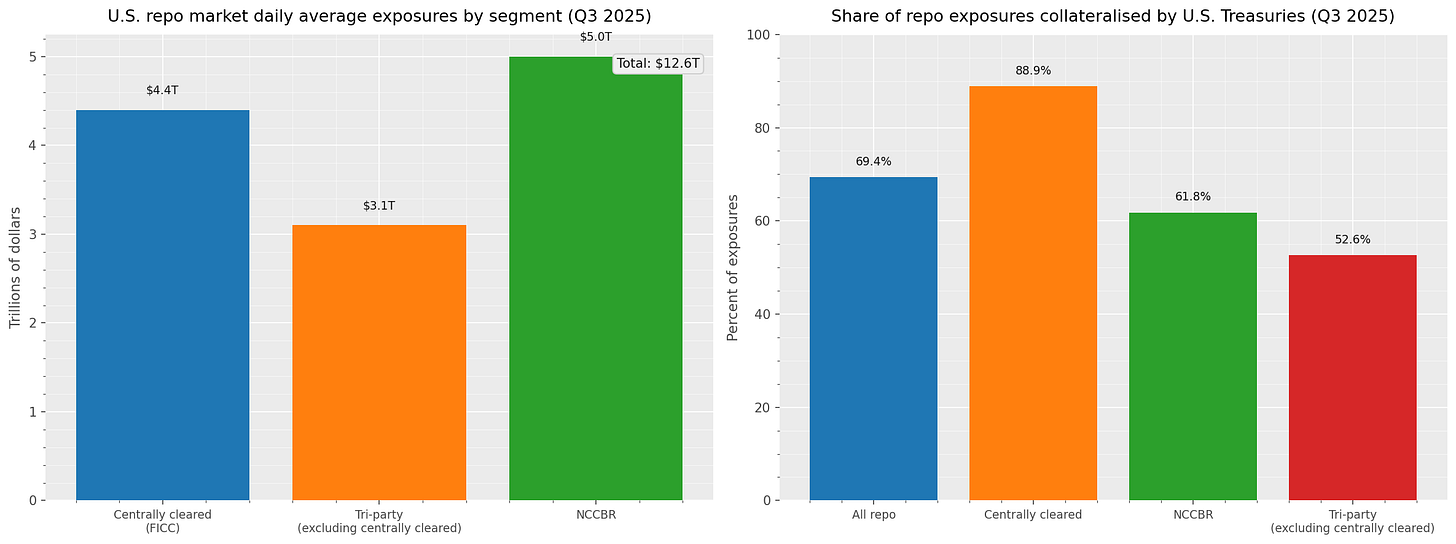

Data from the Office of Financial Research shows estimates that the US repo market average about $12.6 trillion in daily exposures in Q3 2025. A very large segment, about $5 trillion, sits in non-centrally cleared bilateral repo, which is mostly hedge funds, dealers, and private actors that trade directly without a central clearing house. The OFR also estimates that 69.4% of total repo exposures are collateralised by US Treasuries, rising to nearly 90% in centrally cleared segments. US Treasuries are the main asset class with the depth (some $28 trillion outstanding) and liquidity to support a $12.6 trillion funding market.

This is why banks, dealers, funds, clearing houses, and central banks cannot simply dump Treasuries. Institutions need high-quality liquid assets to secure funding, post margin, and satisfy internal and regulatory liquidity constraints. Treasuries sit at the centre of that ecosystem because of their depth and their role as the benchmark collateral in secured funding.

Another reason markets can remain anchored to the dollar, even as domestic political risks rise, are the Fed’s dollar liquidity swap lines and the repo facility for foreign and international monetary authorities, which act as a liquidity backstop for major foreign central banks. Non-US banks, including in Europe, are highly dependent on the dollar as a large proportion of their liabilities, investments, and trade are dollar-denominated. If markets begin to doubt the reliability or neutrality of this backstop, for example because Fed independence is weakened or because access to international liquidity tools is perceived as more discretionary or politicised, it becomes a funding risk for non-US banks and regulators that depend on dollar liquidity in stress.

Conclusion

Markets can be notoriously poor at pricing political tail risks when those risks do not immediately disrupt cash flows or liquidity conditions. It is the boiling frog syndrome. Investors rationalise each incremental step of institutional decay with familiar narratives (the courts will stop him, Congress will push back, it is just rhetoric, etc.). Markets keep pricing the US as a deep and liquid financial system anchored by Treasuries as the premier safe asset and benchmark collateral, and supported by a credible, operationally independent central bank, while underweighting the institutional foundations that make those attributes durable like the rule of law, checks and balances, and democratic norms.

Political and institutional pressures can accumulate without triggering an immediate repricing because the system’s hard features still function day to day, and because there are few substitutes for the global dollar system. But if investors conclude that institutional erosion has crossed a threshold that threatens monetary policy credibility or politicises the Fed’s role, repricing is likely to be discontinuous.